The Sky Takes a Long Time to Congeal

Each morning in Lublin, Poland, thousands of ravens reverse the heavens, braying and bleating like sheep. I watch as birds pulse east, dragging sky behind them.

No pattern of movement repeats. No wing-tracing, no doubled beats.

The sky takes a long time to congeal.

Blue powder clouds, then cream.

A great rush of shapes overhead. Ravens flap, dive, and shriek. They transform the atmosphere into blinking black dots. Earliest language. First beak.

All month, I have filled a tub with water. Mixed dye with cellulose to form blue paper. A single piece of paper takes more than twelve hours to dry. Sticky and viscid. Vulnerable to light, bend, and crinkle.

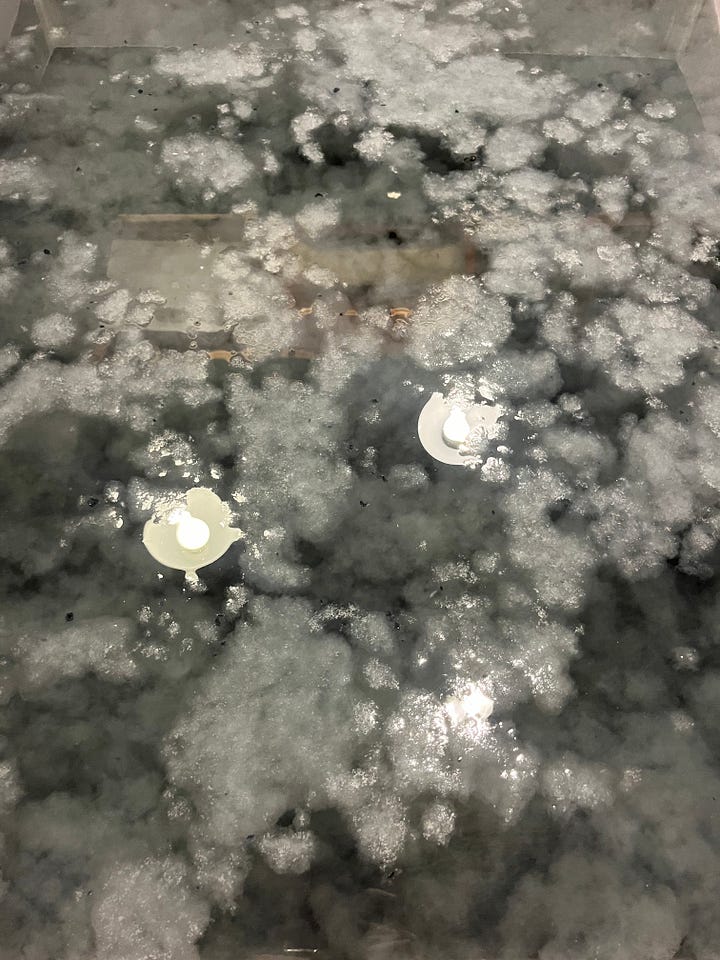

I ground color and cellulose into pulp, then add it to the bath. The process slow and wet. I dip my screen into the pit, which looks, to me, like sky.

Every gesture of my body transforms the sheet—if I take the water from the bath in an uneven manner, the substance clumps across the surface of the page, making a lopsided sheet.

If I separate the wet fibers from the screen too slowly, giant bubbles glop and raise.

If I pull the screen too quickly, holes across the page.

Fragile substance, paper. More than twenty hours of labor to make twenty sheets.

Mix, mix, mix cellulose and dye. Stir, stir, stir, water and pulp. Dip, dip, dip screen into pit.

In the 16th century, a handful of Hebrew books were published in Antwerp on blue paper. The first two editions of the Zohar, printed in Matua and Cremona respectively, were blue. By the early 18th century, a blue paper craze had spread to Central and Eastern Europe, gaining popularity amongst Hebrew printers. Blue for the color of the divine throne.

The Chief Rabbi of Bohemia, David Oppenhemim (1664-1736), ordered his books to be printed exclusively in blue. In Amsterdam, a deluxe edition of the Talmud was run blue. And in Warsaw, the Lebensohn press, active up through 1900, frequently used a light pastel blue for printing Hebrew texts. Blue for messianic fervor. Blue for t’chelet, for sky. The Hebrew writer S.Y. Agnon writes in his book Ha-Simman, “his eyes were like the prayer books printed in Slavita on paper tinted blue.”

Slavuta, which is just past Lviv, in Ukraine—a mere five hour drive from Lublin.

Blue to stir the subtle terrain of the imagination.

Dark flecks of pulp appear on my paper. I will print my poems here, arranging leaden letters and type. A scattering of ravens.

I dip and lift, in-out the water bath.

The sky takes a long time to congeal.

Blue thundering storm.

Yours,

emet

want more of the bird? subscribe below:

poems:

The Way to Keep Going in Antarctica by Bernadette Mayer

Look to the New Moon by Mai Der Vang

I hear a dog who is always in my death by Samuel Ace

Mantric Blizzard as Space by Will Alexander

To Put it Differently by Natan Zach

“There’s no retreat to the mythical island. There never was…” from Schooling Myself, an essay on ethics, Gaza, and autodidactism by Elisa Gonzalez.

Telling the Bees by Will Hunt (one of the best essays I’ve read all year!)

events, etc:

I will have a piece of writing in the inaugural issue of VORTEXT alongside many other writers and friends. VORTEXT is a mail-subscription magazine sent out on equinoxes and solstices from Berlin. Click the image for more information:

I’ve sent this INCREDIBLE conversation to almost every poet I know, in which artist Rachel James interviews Bernadette Mayer about money, poetry, and precarity. A balm to hear Bernadette’s voice gurgling up from the near past.

She died two years ago today, on November 22, 2022—

The next episode of All Saints Poetry Hour airs live on December 19th at 14h CET / 08h EST with Berlin’s Refuge Worldwide Radio! Poet a. Monti and I will be curating a selection of mystical poetyr and song for you from the wintry streets of Neukölln.